The history of disinfection

Of deities and disease

Diseases are no doubt older than humanity itself. People first thought that plagues were brought on by wrathful gods, and later blamed miasmas – toxic emanations from the ground.

The oldest indirect evidence of viruses in Earth’s history is some 289 million years old. In the strangely malformed vertebrae of a lizard-like creature, researchers detected symptoms of a bone disease now commonly assumed to be caused by viral agents.

Settlements established around 12,000 years ago in northeastern Africa bear signs of a pox-like disease that tore through the area. One apparent victim of these diseases was Pharaoh Ramses V (reigned from approx. 1150 to 1145 BCE) – thanks to the Egyptian art of mummification, researchers can study his pox pustules to this day.

Papyri that have been preserved from that time offer exciting insight into the medical understanding of the day. Internal diseases with no detectable cause were generally attributed to supernatural forces or considered the work of wrathful deities. The Smith Papyrus lists magical incantations intended to ward off the pestilences that appeared with the annual Nile flood. External injuries and wounds were a different story. For these, recommendations in the Papyrus included salves containing honey – its adhesive, cleansing, and slightly antibiotic properties would have been very useful in those days.

Hippocrates: Founder of the miasma theory

Hippocrates of Kos (460-377 BCE) is considered the father of the theory of miasmas – the toxic vapors emanating from the ground that were carried by the wind, allowing them to spread disease. Medicine in ancient Greece by and large rid itself of the notion that diseases were a punishment from the gods, and began to assume a more scientific view. The healers of those days were well-traveled, highly respected men who placed a great deal of value on cleanliness.

That perspective can also be seen in ancient Rome. Good overall health and high levels of hygiene were the primary successes of Roman medicine. The first century BCE was also where the idea of living pathogens first arose. In his work entitled On Agriculture, Marcus Terentius Varro (born 116 BCE) – a universal scholar rather than a physician – wrote about tiny, invisible creatures that enter human beings through the respiratory and digestive tracts, where they cause disease.

These silver vinaigrettes were used until the 18th century in order to protect against miasms. They contained small sponges dipped in vinegar.

Even in the Middle Ages, the fear of miasmas led to quarantine-like conditions. Victims of epidemics were hastily buried outside of the city and their belongings burned, and during the plague, cities would place all foreigners in quarantine. To protect themselves from the emanations of sick people, plague doctors wore, in addition to gloves, beak-like masks containing herbs and fluids.

This knowledge was generally not enough to effectively curtail disease outbreaks and pandemics.

The Antonine Plague (165/167 CE) was likely triggered by the smallpox virus. Roman soldiers returning home from the Parthian Wars carried the disease with them from Mesopotamia to Britain. In what was thus a global outbreak, up to 30% of those infected died, for a total of 5 million people.

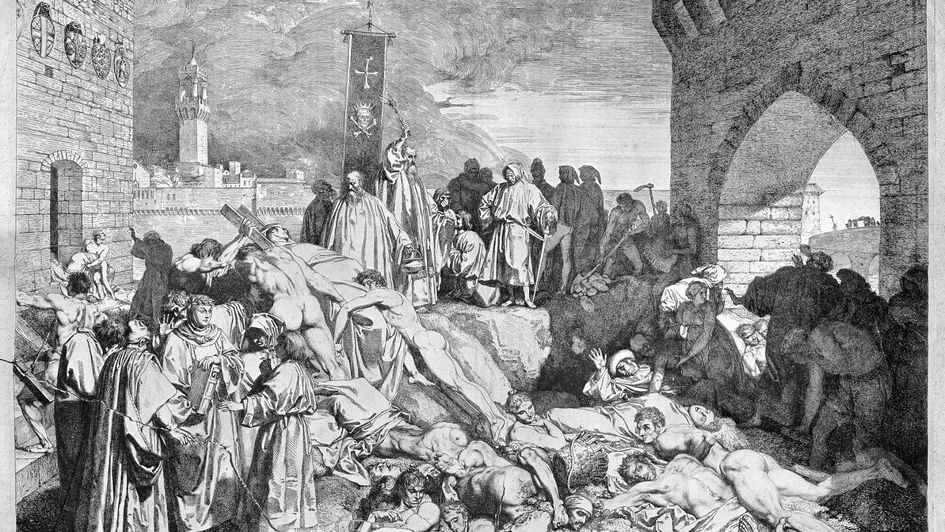

The plague of Florence in 1348 as described in Boccaccio's Decameron. Etching by Luigi Sabatelli.

The Black Death spread throughout large parts of Europe between 1346 and 1353. While measures that included quarantines protected individual districts, the Plague still claimed an estimated 25 million victims – one third of the population at that time.

In the summer of 1889, the Russian Flu spread from central Asia, initially to Russia and then throughout Europe. The steps that were taken – for instance to disinfect the Houses of Parliament in Westminster in May 1891 – still revolved around the notion of miasmas: scrubbing floors with carbolic soap, fumigation with sulfur and camphor, and copious ventilation. On the whole, these efforts had little effect.